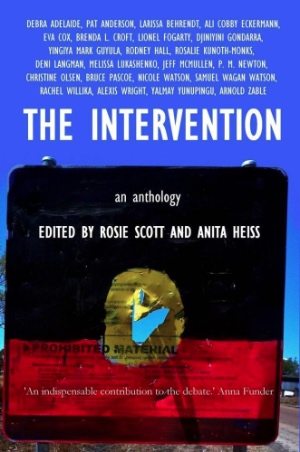

Edited by Rosie Scott and Anita Heiss

Edited by Rosie Scott and Anita Heiss

Launch by the Honourable Alastair Nicholson AO RFD QC

24 September 2015

I have great pleasure in participating in the Melbourne launch of this excellent anthology collected from a wide and expert selection of authors, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Many are household names but others are simple participants or victims of the Intervention. I was touched by the comment of the soldier that in Afghanistan they built schools but in Australia they built police stations, which seemed to me to say it all about the priorities of the Intervention, the spectre of which still hangs over our Aboriginal people like a dark cloud.1 I regard the appointment of one of the creators of the Intervention to the Turnbull Cabinet as a particular irony for a Government that otherwise promises new approaches.

So many of the authors contributing to this book attest to the Intervention's failure and detrimental effects. Christine Olsen has aptly described it as being as if Australia had gone back 100 years.2 No-one has been able to successfully show any significant achievement flowing from it or its 'Intervention Lite' successor, Stronger Futures, but many have pointed out, not only ill effects such as the startling increase in incarceration rates of Aboriginal people and their children, education failures and the attacks upon their traditional ownership of their lands, but more importantly the damaging effect upon the very souls of the Aboriginal people affected.

Rosalie Kunoth Monks writes of the insecurity and loss of belief of people involved in the system as a result of their age old structures being eroded. She speaks of being terrified of losing her people's Aboriginal identity through brutal treatment on their homelands - also a real possibility in Western Australia as well if the Government has its way. Many speak of how shattered they were to be treated in this way by Government and their terror at the involvement of the Army.3

Pat Anderson, who co-chaired the "Little Children are Sacred" reports speaks of the huge lack of Government services that her Inquiry found to have existed for many years prior to the Intervention and which contributed to the problems found by her Inquiry and also of the enthusiasm of the Aboriginal people to work with Government to help overcome the problems that they faced with their children.4

As she says, the most important recommendation of the Report was the first:

"That the NT and Australian Governments commit to genuine consultation with Aboriginal people in designing initiatives for Aboriginal communities to address child sexual abuse and neglect." 5

However the views of the Aboriginal people were never sought, to the shame of the then Government and Opposition. The relevant legislation was rushed through Parliament with the consent of the ALP. It is interesting to note that then Minister for Aboriginal Affairs later admitted that he had not read the legislation before it was passed.

While the primary responsibility for this situation lies with the then Prime Minister John Howard and his Government, the role of the Opposition in its passage, together with its subsequent behaviour when in Government should not be forgotten.

It voted with the Government to pass the relevant legislation, but tried to give the impression that it did so to avoid being wedged with the election looming. As Larissa Behrendt points out in this anthology it ignored its duty as an Opposition party to question and examine such radical and oppressive legislation. She says that the Opposition put out a subtle message that it did oppose the Intervention but voted as it did to avoid being wedged in the coming election. 6

The enormity of the sell-out was further exacerbated by its behaviour when in office when it effectively continued with the Intervention.

For example one would have thought that its first action in Government would have been to reinstate the Racial Discrimination Act as it had promised to do, but this did not happen for four years and then in questionable form.

It continued with the policy of acquiring Aboriginal land on long leases by offering short term bribes of advantage to traditional owners, continuing a tradition of beads and blankets going back to John Batman, while at the same time blackmailing them with threats to either not provide or cut off services.

It ruined working systems for Aboriginal employment and seriously damaged Aboriginal education and health and other Governmental services.

Worst of all it continued so called income protection which was and is a humiliating reversion to policies of control of Aboriginal people redolent of an earlier century.

It did nothing to protect Aboriginal children and young people, which was the ostensible reason for the Intervention.

The fulsome apology offered by Prime Minister Rudd proved to be no more than empty words.

In her astute contribution in the anthology, Yalmay Yunipingu also describes reconciliation, consultation and negotiation, freedom and promise as empty words and this is the real truth of the matter.7

The 'Consultations" in which the Rudd and Gillard governments engaged were laughable and consisted of nothing more than seeking to persuade the Aboriginal people to rubber stamp decisions already taken in Canberra.8

This typifies what Canberra based politicians and departments dealing with Aboriginal people regarded as consultation and why this concept has been so firmly rejected by the Aboriginal people

It is my view that the experience of so called "consultation" by successive Federal Governments has led to a complete loss of confidence in such a process on the part of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to the point that it is questionable whether any agreements based on consultation can ever be legitimate.

The outstanding Aboriginal leader, Djiniyini Gondarra is quoted in the anthology as saying that "the survival of the Aboriginal people relies on changes to the Constitution and the establishment of a Treaty. The Treaty needs to be borne out of the people who have a strong connection with land, culture, spirituality and law rather than being established by government, or a committee formed by government."9

This brings me to the final point that I wish to discuss, which is the way forward. This anthology looks back and there are many valuable lessons to be found in it which can usefully applied to the future, not least being as a guide how not to achieve progress in relations with the Aboriginal people.

I would like to briefly discuss the interaction of possible constitutional change and the making of an agreement or treaty between the Government and Aboriginal people.

Much of the recent discussion as to the future has related to constitutional change and a treaty as if they were opposing concepts. I think it better to regard them as component parts of a single jigsaw. I have difficulty in seeing how constitutional change of itself can meet the legitimate aspirations of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It is difficult in the context of a constitutional amendment to descend to the sort of detail that can be contained in an agreement. To succeed, a constitution amendment must be succinct and easily understood.

At the same time I see difficulties about an agreement or treaty achieving what is sought on its own. While there are difficulties I can envisage that such an agreement is possible. However without constitutional recognition it would be either unenforceable unless enshrined in legislation and then be likely to become unenforceable depending on legislative whim. We saw this in the way that the Howard Government and its Labor successors treated the Racial Discrimination Act.

As to the treaty issue we should remember that the concept of a treaty has been around for some time. Prime Minister Hawke in fact agreed to negotiate a treaty with Aboriginal people in 1988 and later reneged on it. It later lost all traction during the negative period of the Howard Government from 1996-2007.

However the issue was revived early in 2008. At the 2020 summit convened by Prime Minister Rudd in 2008 I participated in the Indigenous stream along with other Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, including Professor Sarah Maddison, where the concept of a treaty was discussed.

In her book Black Politics10 she records witnessing an emerging consensus on the issue of legal recognition, preceded by a commitment to a national dialogue on the issue. She notes that there was no division between those wanting a treaty and those wanting constitutional reform. As she correctly records it, by the end of the first day the 100 delegates had agreed on three priority areas, each of which went to the question of unfinished business.

These were first, the initiation of a national dialogue towards forming a legal basis for the relationship between Indigenous and non- Indigenous Australians. The form of the arrangement was left open although by the end of the second day a preference for constitutional change seemed to have evolved.

Secondly the group envisaged the creation of a reconstruction fund perhaps based on a percentage of GNP, which would be directed to the rebuilding of core services in Aboriginal communities.

Thirdly, prioritizing the development of a new cultural framework for Australia that places Aboriginal culture at the centre through the creation of a Cultural Heritage Authority and new cultural symbols.11

I realise that the first conclusion rather favoured the argument for constitutional change as opposed to a treaty or agreement. However for the reasons stated above I think that both are necessary. In any event I found it encouraging that such a widely disparate group of people could conduct a sensible dialogue over two days and arrive at a reasonable consensus to go forward. In this dialogue no one was negotiating from a position of power and for me at least, it gives a pointer to what might be achieved by such a process on a larger scale.

Finally, I take great pleasure in formally launching the Anthology today. It should be compulsory reading for politicians and bureaucrats and anyone interested in addressing the problem of relations between Indigenous and Non- Indigenous Australians.

Endnotes

1 The Intervention, Scott and Heiss; 'concerned Australians' 2015

2 Ibid. Olsen C, Closing the Gap 57

3 Ibid. Kunoth Monks R, Reflections on the Intervention, 15-17

4 Ibid. Anderson P, The Intervention, Personal Reflections 31-2

5 Anderson P and Wild R, 2007 Little Children are Sacred Northern Territory Government Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse 2006

6 Ibid. Behrendt L, The Dialogue of Intervention 72-3

7 Ibid. Yunipingu Y, Human Rights and Social Justice Award - Keynote Speech Excerpts 230

8 Nicholson A (2011) 'Open letter to the Hon Jenny Macklin MP' signed by Alastair Nicholson on behalf of 20 other signatories, 27 June; Nicholson A, Behrendt L, Vivian A, Watson N and Harris M (2009) Will They be Heard? A Response to the NTER Consultations June to August 2009 Research Unit, Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology, Sydney; Nicholson A, Watson N, Vivian A, Longman C, Priest T ,De Santolo J, Gibson P, Behrendt L and Cox E (2012) Listening But Not Hearing; A Response to the NTER Stronger Futures Consultations June to August, 2011 Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, University of Technology, Sydney; Partridge, Maddison and Nicholson Human Rights Imperatives and the failings of the Stronger Futures consultation process; 18(2)Australian Journal of Human Rights (AUJIHRIGHTS) 2012;

9 Ibid Gondarra D, Quotes from Speeches on the Intervention 47

10 Maddison M, Black Politics, Inside the Complexity of Aboriginal Political Culture. Allen&Unwin 2009